Who Has Osteoporosis?

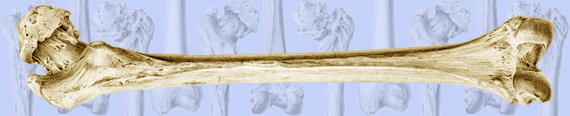

Femoral neck fractures can result in severe impairment of mobility and lifestyle, and in the elderly they are also associated with a mortality rate that can exceed 20% within two years of fracture (Boonen et al., 2004; Adachi et al., 2010; Ma et al., 2011). It is estimated that nearly 30 million people in the United States have significant bone loss, and nearly 10 million of them severe enough to meet the definition of osteoporosis (Lane et al., 2006). Most of those who have this disease are women. According to many authors those most at risk appear to be white women.

What is the Result of Osteoporosis?

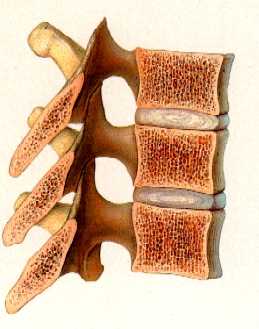

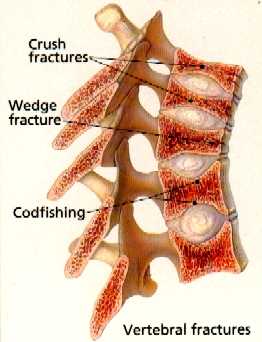

There are an estimated 1.5 million (Lane et al., 2006) bone fractures per year resulting from bone loss. These are most likely vertebral compression fractures — about 650,000 — during which the cylindrical body of the backbone compresses down, causing pain and disability.

Normal Spine

Spine With SevereOsteoporosis

Next are the most devastating, hip fractures – about 300,000 per year (Lane et al., 2006). Forearm fractures and those of other sites are also common. These fractures are seen with little or no trauma — in fact, it is often wondered whether or not the patient “fell and broke their hip” or actually “broke their hip and then fell.” The patient frequently thinks they “must have tripped over the rug” — but it’s a rug which they have been walking over for ten years! The mere act of stepping or mildly stumbling was enough to break their hip.

Likelyhood of a Fracture

The odds of an American woman getting a hip fracture at some time in her life appears to be about 18%; a vertebral body fracture about 16% (Melton et al., 1992).

Consequences of a Fracture

The most devastating consequence of a hip fracture is death; nearly 25% of elderly patients with a hip fracture die within 2 years of the event. For those who live, there is a significant loss of mobility. This sets up the patient for potential rapid deterioration. The financial cost to our society of these fractures is astronomical. There are clearly compelling reasons to prevent them whenever possible.

What Causes Osteoporosis?

Bone Turnover

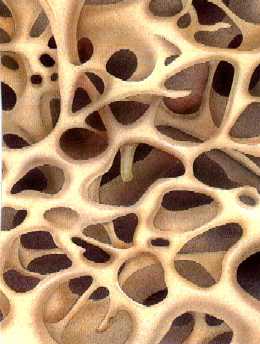

The matrix of bone is constantly being turned over — bone is broken down and the minerals released into the body, and new bone is made. Cells called osteoclasts break down the bone and cells called osteoblasts build new bone. Different factors affect each, and a difference in the rates of rebuilding and tearing-down of bone results in bone growth or bone loss.

Normal Matrix

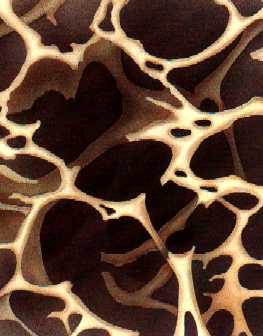

Matrix With Severe Osteoporosis

Images courtesy of Merck, Inc.

Risk Factors:

- Increasing risk:

- Older age.

- Caucasian race.

- Lighter weight (for hip especially).

- Younger age at menopause.

- Low estrogen conditions when younger (very athletic, thin, few menstrual periods)

- Alcohol use.

- Tobacco use.

- Family history of osteoporosis.

- Corticosteroid (cortisone) use.

- Thyroid replacement – especially if too high.

- Anticonvulsant medications.

- Malabsorption problems.

- Lack of exercise.

- Dietary deficiencies, excess protein?

What is Your Risk?

Diet

The issue of diet is very controversial. It is fairly well understood that a low intake of Calcium and Vitamin D can predispose to osteoporosis. It is probably useful, especially for those at higher risk, to get at least 1200mg of calcium per day, and at least 500 Mg of Vitamin D. Some have proposed that our high-protein diet is partly responsible for this disease. Many cultures which have a low-protein diet have a low-incidence of osteoporosis. It has been shown that consumption of excess protein results in larger urinary losses of calcium. Calcium supplements are often recommended for those at risk – review the page on calcium supplements and dietary calcium.

Evaluating Osteoporosis

There are many means of measuring bone density, ranging from simple x-rays to CT scans. Special instruments which measure the absorption of low-intensity x-rays as they pass through bone are probably the most accurate. The most common one used these days is the dual x-ray absorptiometry, or DEXA. This device is usually used to measure density at the hip and in the lower back.

Bone density is measured in relationship to the average bone density of a pre-menopausal woman, expressed in terms of standard deviation (SD) units. Normal bone density is that between +1 and -1 SD of young women. Osteopenia is defined as bone density between -1 and -2.5 SD of that of a young woman. Osteoporosis is defined as bone density lower than -2.5 SD of that of a young woman.

Predictive Value of Bone Density

Every decrease of spinal bone density of 1 SD increases spine fracture risk by two. Every decrease of hip bone density of 1 SD triples hip fracture risk. On this website in “Publications” see our paper on evaluation bone density using DEXA scans and the “OST” measurement (Skedros et al., 2007).

Estrogen

Estrogen decreases bone breakdown, or resorption. Estrogen replacement therapy after menopause has been shown to increase bone density 2 to 3% and to slow the progression of osteoporosis. Spine and hip fracture rates for women who receive post-menopausal estrogen supplements is shown to be about half that of those who do not. Women who have had lowered estrogen levels earlier in life – either through early menopause (natural or due to removal of the ovaries) and those who are thin and athletic and have missed periods have a higher risk. Young athletic women who have missed periods are now being put on birth-control pills to give them sufficient estrogen to maintain bone mass.

Other risks and benefits of estrogen

Estrogen also helps in the treatment of menopausal symptoms, and has been shown to significantly lower the risk of heart disease. It may also lower the risk of colon cancer and delay the development of Alzheimer’s disease. The risks include increased rate of breast cancer and cancer of the uterus. The later has been shown to be greatly reduced by balancing the estrogens with progesterone.

Non-Estrogen Treatments for Osteoporosis

Calcitonin, a hormone which decreases bone resorption, has been available for a number of years. It has been shown to increase bone density in the spine, and even to decrease pain associated with spinal osteoporosis, but it is unclear to what extent it improves bone density in the hip. It is now available as a once-a-day nose spray.

Alendronate – “Fosamax” is a drug in the class called biphosphonates which also decreases bone resorption (Papapoulos, 2013). It has been shown to increase bone density in both the spine and hip, and to decrease fractures over three years. Although it is generally a safe medication, it tends to cause potentially severe acid reflux into the esophagus. It is also not absorbed with food in the stomach. Therefore, the requirements for taking it are to take it with a large glass of water on an empty stomach first thing in the morning, not to eat for 30 minutes, and NOT to lie back down after taking it.

There are other experimental treatments, and ones that may work but have not been studied to a great extent. For example, diuretics such as hydrochlorothiazide, used for hypertension, have long been used to help prevent calcium-containing kidney stones in those at risk by reducing calcium excretion in the urine. These medications have small positive benefits in treating osteoporosis (Bolland et al., 2007). Hence, these medications can be included in a list of potential medications being considered for treating high blood pressure in a woman at risk for osteoporosis, it might make sense to use them.

References

Adachi JD, Adami S, Gehlbach S, Anderson FA, Jr., Boonen S, Chapurlat RD, Compston JE, Cooper C, Delmas P, Diez-Perez A, Greenspan SL, Hooven FH, LaCroix AZ, Lindsay R, Netelenbos JC, Wu O, Pfeilschifter J, Roux C, Saag KG,

Sambrook PN, Silverman S, Siris ES, Nika G, Watts NB. 2010. Impact of prevalent fractures on quality of life: baseline results from the global longitudinal study of osteoporosis in women. Mayo Clin Proc 85:806-813.

Bolland MJ, Ames RW, Horne AM, Orr-Walker BJ, Gamble GD, Reid IR. 2007. The effect of treatment with a thiazide diuretic for 4 years on bone density in normal postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 18:479-486.

Boonen S, Autier P, Barette M, Vanderschueren D, Lips P, Haentjens P. 2004. Functional outcome and quality of life following hip fracture in elderly women: a prospective controlled study. Osteoporos Int 15:87-94.

Lane JM, Serota AC, Raphael B. 2006. Osteoporosis: differences and similarities in male and female patients. Orthop Clin North Am 37:601-609.

Ma RS, Gu GS, Huang X, Zhu D, Zhang Y, Li M, Yao HY. 2011. Postoperative mortality and morbidity in octogenarians and nonagenarians with hip fracture: an analysis of perioperative risk factors. Chin J Traumatol 14:323-328.

Melton LJ, 3rd, Chrischilles EA, Cooper C, Lane AW, Riggs BL. 1992. Perspective. How many women have osteoporosis? J Bone Miner Res 7:1005-1010.

Papapoulos SE. 2013. Bisphosphonates for Postmenopausal Osteoporosis. In: Rosen JR, editor. Primer on the Metabolic Bone Disease and Disorders of Mineral Metabolism, Eighth Edition: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p 412-419.

Riek AE, Towler DA. 2011. The pharmacological management of osteoporosis. Mo Med 108:118-123.

Saag KG, Shane E, Boonen S, Marin F, Donley DW, Taylor KA, Dalsky GP, Marcus R. 2007. Teriparatide or alendronate in glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 357:2028-2039.

Skedros JG, Sybrowsky CL, Stoddard GJ. 2007. The osteoporosis self-assessment screening tool: a useful tool for the orthopaedic surgeon. J Bone Joint Surg Am 89:765-772.