Overview

Ankle injuries are one of the most common injuries in sports. It is estimated that there are over 23,000 ankle sprains per day in the United States. Most of these injuries are uneventful and heal with time, but approximately 20% go on to have recurrent instability.

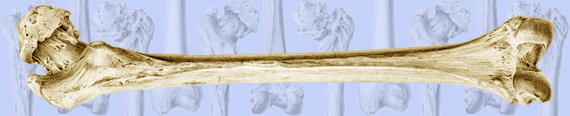

Anatomy

The ankle joint is formed by the articular surfaces of the tibia, fibula and talus. The ankle joint is a hinged joint involved in ankle dorsiflexion and plantarflexion. Both medial and lateral ligaments stabilize the ankle to prevent excessive inversion and eversion of the ankle.

Lateral and medial ankle anatomy

Three main ligaments provide lateral ankle stability: the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL), the posterior talofibular ligament (PTFL), and the calcaneofibular ligament (CFL). The ATFL and the CFL are the two most clinically significant ligaments of the lateral ankle. The ATFL originates on the anterior distal fibula and inserts on the neck of the talus. It is the primary restraint to inversion with the foot in plantarflexion. The CFL originates on the tip of the lateral malleolus and attaches to the lateral calcaneus. It is the primary restraint to inversion with the foot held in dorsiflexion.

The deltoid ligament provides medial ankle stability. The deltoid ligament is composed of four structures: the anterior talotibial, posterior talotibial, tibiocalcaneal, and tibionavicular ligaments.

The roof of the ankle joint is often referred to as the ankle mortise. The mortise is composed of the tibial plafond and the medial and lateral malleoli. The ankle mortise integrity is maintained by the syndesmosis, which is composed of four structures: the anterior tibiofibular ligament, posterior tibiofibular ligament, transverse tibiofibular ligament, and the interosseous membrane.

Mechanisms of Injury

Lateral ankle sprains are the most common ankle injuries. Most ankle sprains occur when landing on a plantarflexed, inverted foot. Usually the ATFL is injured first followed by the CFL and PTFL. Isolated CFL injuries have been described with dorsiflexion, inversion mechanisms. Deltoid ligament and syndesmosis injuries occur with an external rotation, eversion injury. Isolated ATFL sprains are by far the most common (60%), followed by combined ATFL/CFL sprains (20%), syndesmotic injuries (1-10%) and deltoid sprains (2.5%).

Classification

Ankle sprains have been classified as Grade I, II, or III. Grade I injuries involve stretching of the ligament. There is no instability of the ankle with Grade I tears and patients are often able to ambulate and have minimal swelling and tenderness. Grade II sprains represent a partially torn ligament. There is associated loss of motion and difficulty ambulating without support. Ankle instability may be present. Grade III sprains represent complete tears of the ligaments. Ankle function and stability are compromised. Ambulating is impossible without pain.

History/Physical Examination

As always, it is essential to obtain a thorough history. Mechanism of injury, previous ankle injuries, and post injury activity level are just a few questions that should be addressed. It is important to remember that there are other bony and soft tissue structures around the ankle and foot that could be injured.

Physical exam of the ankle begins with inspection and palpation. Areas of swelling and ecchymosis should be noted and careful palpation of the ligaments and bony structures should be performed to localize the site of injury.

Anterior drawer test

Talar tilt test

There are numerous tests described to test ankle stability. The ankle anterior drawer test assesses the integrity of the ATFL and measures anterior talar translation. The test is performed by stabilizing the distal tibia with one hand and pulling the heel forward. Anterior translation of greater than 4mm compared to the contralateral side is considered a positive test. The talar tilt test is also used to test the lateral ankle, specifically the calcaneofibular ligament. It is performed by inverting the ankle and estimating the tilt of the talus in reference to the tibial plafond. A positive test is tilt greater than 6º difference compared to the contralateral side. The syndesmosis is tested with the external rotation test and the squeeze test. The external rotation test is performed by externally rotating the foot while in plantarflexion. The test is positive if pain is elicited at the syndesmosis. The squeeze test is positive if ankle pain is elicited with midcalf tibia and fibula compression.

Imaging

The standard ankle radiographic series includes an anteroposterior, lateral and mortise view. Ankle stress views can provide further information in the ankle sprain workup. The radiographs should be assessed for widening of the mortise or syndesmosis, avulsion fractures, osteochondral injuries, and other bony injuries. An MRI may be helpful for further evaluation of the soft tissues.

Treatment

Stable (Grade I and II) ankle sprains are treated with Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation (RICE). Protected weight bearing should be continued until nonpainful and the patient is ambulating without a limp. Therapy begins with early pain free range of motion and is gradually increased to strengthening and proprioceptive training. Usually patients will return to activity in 2-4 weeks. Unstable (Grade III) ankle sprains may also be treated non-operatively although the rehabilitation time is much longer. Return to activity is usually 4-10 weeks.

Repeated lateral ankle sprains may lead to chronic lateral instability of the ankle. Patients with chronic instability present with pain, giving way and functional instability of the ankle. The patient presents with peroneal weakness, lateral tenderness, and lateral ankle laxity. Treatment should begin with conservative measures; however, operative repair or reconstruction of the torn ligaments may be necessary.

Grade III syndesmosis ankle injury treated with screw fixation

A syndesmosis injury, or “high ankle sprain”, is an injury seen commonly in football players. A positive squeeze test and external rotation test may indicate a syndesmotic injury. Grade I injuries have clinical findings but negative stress radiographs. Grade II injuries have no widening on plain radiographs but positive stress radiographs. Grade III injuries show widening on plain radiographs. Grade I and II high ankle sprains may be treated with non-operative measures. Return to activity usually takes 4-10 weeks. Grade III injuries are treated surgically with syndesmotic screw fixation. Return to sport usually takes 4-6 months.