Overview

Articular cartilage plays an important role in joint load bearing and motion. The cartilage surface provides joints with a smooth, lubricated surface that minimizes friction. Its biomechanical properties are directly related to its composition. Articular cartilage is composed mainly of water (65-80%), type II collagen (10-20%), and proteoglycans.

Articular cartilage injuries can either be from traumatic or atraumatic (inflammatory disease, osteoarthritis) causes. When articular cartilage is damaged, it has a limited ability to repair itself. Adult articular cartilage has difficulty repairing itself due to its lack of undifferentiated cells and blood supply.

Classification

The Outerbridge Classification system is often used to describe articular injuries. The following is a simplified description of the classification of articular injuries.

Grade I: softening.

Grade II: fibrillation.

Grade III: fissuring.

Grade IV: erosion of the cartilage exposing subchondral bone.

History/Physical Exam

Cartilage injuries can present in many different ways. Patients may or may not cite a traumatic injury. Degenerative lesions may present as intermittent pain that is localized to the medial or lateral joint line. Patients with injuries to the cartilage with loose bodies may complain of clicking, catching or locking. They may have crepitance with range of motion.

Imaging

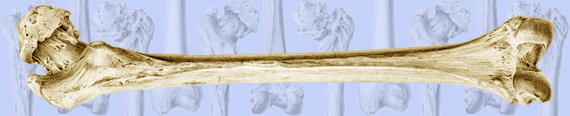

Full thickness cartilage defect

Radiographs are important in the work up of cartilage injuries. Chronic degenerative cartilage wear will show radiographic changes including joint space narrowing, subchondral cysts, flattening and sclerosis of the condyles, and osteophytic changes. An MRI may be helpful in determining the extent of the cartilage lesion. It is not too helpful in the workup of chronic degenerative changes but can be helpful in locating focal cartilage injuries and identifying potential loose bodies.

Treatment

Treatment of focal articular injuries depends on patient age as well as location, thickness, and size of the defect. Symptomatic partial thickness injuries may be treated with a conservative debridement with removal of articular flaps and impending loose bodies. There are numerous surgical procedures used to treat full thickness cartilage injuries including procedures that stimulate healing, osteotomies, and autogenous/allograft tissue transfers.

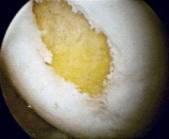

Microfracture of full thickness cartilage defect

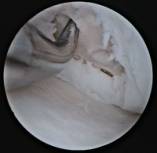

Autologous osteoarticular transplantation: schematic and intra-operative view

Various techniques are described to treat small full thickness cartilage injuries. These include debridement, drilling, microfracture, and abrasion arthroplasty. All of these techniques penetrate the subchondral bone and cause bleeding. The bleeding stimulates mesenchymal stem cells and promotes repair of the defect with fibrocartilage. Fibrocartilage, which is primarily type I collagen, has inferior wear characteristics compared to the original hyaline cartilage.

If there is a notable limb malalignment, an osteotomy may be performed to transfer the weight bearing force away from the cartilage defect. Osteotomies are used more frequently in patients with large unicompartmental defects with an associated limb malalignment.

There are many procedures described for the treatment of large full thickness cartilage defects. Larger focal defects may be replaced with either autologous or allograft tissue.

Autologous chondrocyte transplantation

Autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) is a surgical procedure used for the treatment of full thickness articular injuries. ACI is a two-stage procedure. The first stage requires cartilage harvest from the patient. This cartilage specimen is then sent to the laboratory and the chondrocytes are cultured and grown. In the second stage of the procedure, a periosteal flap is sewn over the cartilage lesion and the cultured chondrocytes are then injected under the flap. Early histologic studies have shown a hyaline type II collagen like repair with ACI.

Autologous osteoarticular transplantation is a procedure that transfers normal cartilage to the damaged area. The circular osteoarticular plugs are harvested from a non weight-bearing region of the knee and transplanted into the defect. The benefits of this procedure are that there is no risk of disease transmission and the defect is filled mainly with hyaline cartilage. However, the supply of autologous cartilage is limited and there are concerns about donor site morbidity.

Allograft cartilage may be used and is typically reserved for very large cartilage defects. Allograft specimens eliminate donor site morbidity and graft size is typically not a problem. However, allograft tissue has less potential to heal compared to autogenous tissue and there is also the small risk of disease transmission.

Osteochondritis Dessicans

Osteochondritis dessicans (OCD) is a specific term that refers to a subchondral bone/cartilage lesion. OCD lesions can be found in any joint but is most common in the knee, elbow, patella, and talus. There are numerous potential etiologies including traumatic, growth disorders, ischemia, and endocrine problems. In the knee, the OCD lesions are usually found in the lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle. Loose bodies may be associated with OCD lesions. Patients often complain of knee pain, swelling, and may have catching or locking if the OCD lesion separates. OCD lesions are seen on plain radiographs. CT or MRI scans can be helpful in determining the size and continuity of the lesion.

OCD lesions are seen in both children and adults. Most OCD lesions in the skeletally immature heal spontaneously while adult onset OCD lesions have a much higher probability of developing secondary degenerative changes.

The goals of treating OCD lesions are to promote healing of the bony lesion and preserve the overlying cartilage. Intact lesions in the skeletally immature patient are treated with activity modification. Operative management in the younger patient is pursued if conservative management fails or if the OCD lesion is displaced. Treatment ranges from drilling to stimulate subchondral bone healing to fixation of the fragment. Treatment of the skeletally mature is similar to children although the results are less successful. Drilling may be performed for intact lesions and displaced lesions may be reduced and fixed. However, if lesions are irreparable, options such as autologous osteochondral transplantation, allograft reconstruction, or ACI may be necessary.

OCD lesion of the medial femoral condyle