Cerebral Palsy (CP) is a term referring to a static encephalopathy occurring secondary to a brain lesion either caused prior to birth (prenatal), at birth (perinatal) or after birth (postnatal). These are generally hypoxic in nature, but can also be due to congenital brain malformation. The incidence is 2:1,000 births and is increasing slightly as more premature infants (particularly before 32 weeks) are saved by modern NICU practice. Pre and perinatal causes are by far the most common etiology, with the size of the lesion correlating to the amount of deficit.

CP may be either spastic (80%) or athetoid/hypotonic due to extrapyramidal injury, (often secondary to Rh incompatability). In addition to motor disorders, developmental delay, blindness, seizure activity, malnutrition and other GI problems can occur. Some children may also have ataxia due to cerebellar involvement.

Anatomic classification of cerebral palsy is determined by location of involvement. Quadriplegia is involvement of all 4 limbs or “total body involvement”; these children are also the most likely to suffer from digestive malfunction, seizure disorders and developmental delay. Diplegia refers to involvement of the lower extremities without significant upper extremity malfunction. Hemiplegia involves one side of the body (clear right or left handedness before age 2 ½ is often a clue); these children are usually very high functioning. Triplegia (three limb) and monoplegia (one limb) are rare and usually are slight variations of quadriplegia or hemiplegia respectively.

Diagnosis

For diagnosis and evaluation of CP the pregnancy, birth history and developmental history of the child are all extremely important. History of prematurity, the need for prolonged hospital stay or supplemental oxygen, Apgar score <5 at 10 minutes or neonatal seizures all point to anoxia. Children generally roll over at three to five months, sit at five to seven months, pull to stand at seven to ten months and walk by 17 months. Failure to reach these basic milestones or prolonged primitive reflexes (Moro, grasp, or absence of step or parachute reflexes) signifies gross motor developmental delay. In older children the motor problems can be subtle; toe walking and clonus, drawing up the upper extremity while running, left-handedness with right foot stiffness are all signs noted in a less involved child.

Involvement of a neurologist, at least for one initial evaluation is important: there are alternative causes of spasticity, which can be inherited, or progressive. These must be assessed for accurate treatment. Finally any child who is deteriorating in function must be carefully reviewed and referred to neurology; CP is a static non-progressive state, deteriorating clinical behavior suggests a diagnosis other than CP.

Prognosis

Children who do not independently sit by 24-30 months have a poor prognosis for ambulation. Children who have not walked independently by six years will probably always need assistive devices. It is very important to steer focus to the child’s strengths and assure comobidities such as GI, speech, and seizure dysfunction are carefully treated in addition to their orthopaedic needs. Because of this “CP clinics” with an orthopaedist, orthotist, therapist (speech, OT, PT) developmental pediatrician, neurologist and rehab doctors are often created to set up “one stop shopping” for the families of CP children. The cross education from multiple services is helpful not only for the families but also for each caretaker.

Treatment

Treatment focuses on treatment of spasticity and deformity. In general contractures secondary to spasticity can be dynamic or fixed. Botox/Phenol injections, Baclofen (either oral or in pump form), selective dorsal rhizotomy, physical therapy and bracing are excellent modalities for dynamic contractures as they modify spasticity. Fixed contractures (those not passively correctable) usually require surgical tendon lengthening. For bony deformity, i.e., hip subluxation, scoliosis, etc., orthopedic intervention, such as osteotomies, with or without concomitant soft tissue lengthening is done. Gait lab evaluation can be extremely helpful in these complicated patients as long as they are able to follow instruction (generally over four years of age) and are able to walk with or without aid. Timing of surgical intervention is also critical; in soft tissue lengthening, surgery done too early may need to be repeated as the child grows. On the other hand, not approaching fixed contractures in a timely fashion can prematurely lead to bony deformity necessitating a much larger surgery such as osteotomy. Controlled studies are difficult to find, as the CP patient population is so heterogeneous, therefore careful and repeated evaluation is essential to the most appropriate treatment.

Specific Orthopaedic Interventions

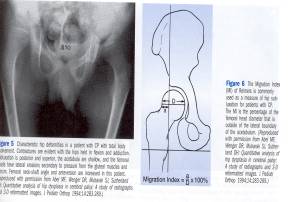

Tightness of the hamstrings, adductors and iliopsoas is frequently seen in children with spasticity. Lengthening of these tendons is advised if the spasticity is limiting function or if subluxation of hips is over 30%. (This is measured as 30 % of the femoral head lateral to Perkins line, which is a perpendicular line drawn through the lateral edges of the acetabulum).

The percent uncovered is termed Reimer’s index, and is also used as terminology in developmental dysplasia of the hip. Studies have shown that in children less than five years who have subluxation, muscle balancing procedures such as tendon lengthening can actually reverse subluxation as well as improve function.

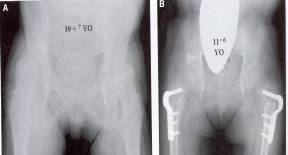

For children over five years with significant subluxation (>30%) osteotomy may be done with tendon lengthening. In the rare, severely compromised child with quadriplegia if the hip is symmetric and not leading to pelvic obliquity it may at times be left alone. However, most children have asymmetric or a “windswept” deformity, with one hip adducted and another abducted. In these children unilateral and often bilateral osteotomies are required. Not only does the subluxated hip progressively worsen over time worsening the pelvic obliquity, ease of perineum care and scoliosis, but also it may dislocate and become painful. Over 50% of these children will eventually have pain, and once the acetabulum is dysplastic and the articular cartilage of the head compromised we have no easy answers. Neither arthroplasty nor arthrodesis (fusion) are good options in severe spasticity leaving hip resection the only option, and not a particularly graceful one.

To balance forces bilateral varus rotational osteotomies (VRO’s) are more frequently chosen, often with soft tissue balancing. For subluxation over 60%, an open reduction of the hip (opening the joint, removing obstacles and tightening the stretched capsule) and even acetabular osteotomy may also be required.

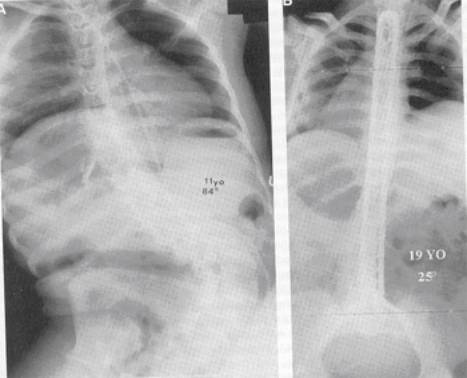

Spine

Paralytic scoliosis is present primarily in children with spastic quadriplegia; as many as 60% may have some curvature. The pattern is often “C” shaped rather than the classic “S shape seen in idiopathic scoliosis. The curve often continues down to the pelvis either secondary to or causing pelvic obliquity which can make treatment of the hip deformity difficult without addressing the back. Bracing can be difficult due to the stiffness of the curve, its often relentless progression despite bracing can the thoracic weakness of these children leading to restrictive pulmonary changes. Surgery is often required if the curve becomes >50º or rigid pelvic obliquity is worsening hip subluxation. The sitting balance of spastic children with large curves is compromised making chair fitting complex. Often the children “give up an arm” by using on arm to balance themselves while sitting therefore compromising upper extremity function as well.

Surgery includes a posterior spinal instrumentation and fusion (PSIF) often to the pelvis (Galveston technique). Anterior releases may be needed for stiff curves over 70 – 80%, which do not correct substantially with traction. Bone grafting is done with a combination of allograft and autograft. These are massive surgeries for children who are often severely compromised. Careful pre-op evaluation and planning (i.e., pulmonary status, need for blood products, need for post-op ICU care, etc.) must be undertaken to make surgery as safe as possible.

Foot deformities

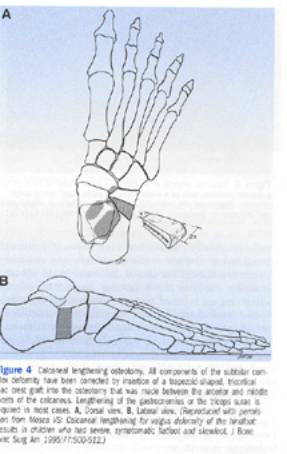

In young children with flexible deformities bracing with or without Botox injections may functionally control deformity. These most commonly are equinus, equinovarus, Cavovarus, planovalgus, and bunions either dorsal or hallux valgus. For equinus the tendo Achillis in total or only the gastroc alone can be lengthened. The gastroc alone is lengthened if dorsiflexion to neutral position is possible with the knee flexed (indicating soleus is not contracted) but not when the knee is extended (which stretches the gastrocnemius). For planovalgus, which often goes with hallux valgus and out-toeing, the Achilles can be occultly tight, the peroneus brevis also tight, and the calcaneus may need to be lengthened.

Cavovarus and equinovarus may need plantar releases (cavovarus) or Achilles releases (equinovarus) to correct the hindfoot, with either anterior or posterior tibialis lengthening or transfer to balance the forefoot. These deformities are more common in ambulatory children.

Hallux valgus and dorsal bunions are more common in minimally or no-ambulatory children. They are recalcitrant to most soft tissue balancing and/or osteotomies; frequently MTP fusion is performs as a definitive procedure once skeletal maturity is adequate.

Upper Extremity

Upper extremity contractures are frequent in CP and are treated by the hand surgeons rather than the pediatric orthopaedist. As with other deformities Botox may be used early on, but as fixed contractures develop surgical intervention may be required. The child must have enough awareness of the extremity (i.e., use it as a “helper hand”) to warrant treatment.

Conclusion

In conclusion CP is a very complex cohort of related but different clinical presentations of a static spaticity or hypotonia. More advanced reading can be found in Tachdjian’s Pediatric Orthopedics, or Lovell and Winter’s Pediatric Orthopedics.